The toe bone’s connected to the foot bone. The foot bone’s connected to the anklebone. The anklebone’s connected to the knee bone. And what holds them together all the way up to the head bone is connected to your diet. Like all body tissues, bones are constantly being replenished. Old bone cells break down, and new ones are born. Specialized cells called osteoclasts start the process by boring tiny holes into solid bone so that other specialized cells, called osteoblasts, can refill the open spaces with fresh bone. At that point, crystals of calcium, the best-known dietary bone builder, glom onto the network of new bone cells to harden and strengthen the bone.

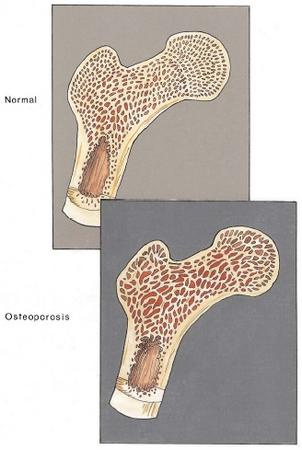

The toe bone’s connected to the foot bone. The foot bone’s connected to the anklebone. The anklebone’s connected to the knee bone. And what holds them together all the way up to the head bone is connected to your diet. Like all body tissues, bones are constantly being replenished. Old bone cells break down, and new ones are born. Specialized cells called osteoclasts start the process by boring tiny holes into solid bone so that other specialized cells, called osteoblasts, can refill the open spaces with fresh bone. At that point, crystals of calcium, the best-known dietary bone builder, glom onto the network of new bone cells to harden and strengthen the bone.Calcium begins its work on your bones while you’re still in your mother’s womb. But it’s not the only mineral at play. You should also think zinc. Based on a survey of 242 pregnant women in Peru, where zinc deficiency is common, Johns Hopkins researchers found the babies born to women who got prenatal supplements with iron, folic acid, and zinc had longer, stronger legs bones than did babies born to women who got the same supplement minus the zinc. After you’re born, calcium continues to build your bones, but only with the help of vitamin D, which produces a calcium-binding protein that enables you to absorb the calcium in the milk Mummy feeds you. To make sure you get your D, virtually all milk sold in the United States is fortified with the vitamin. And because you may outgrow your taste for milk but never outgrow your need for calcium, calcium supplements for adults frequently include vitamin D. But vitamin D isn’t milk’s only contribution. Remember the iron in the Peruvian (and American) prenatal supplements? It isn’t there by accident. Iron increases the production of collagen, the most important protein in bone. Milk contains lactoferrin (lacto = milk; ferri = iron), an iron-binding compound that stimulates the production of the cells that promote bone growth. When researchers at the University of Auckland in New Zealand added lactoferrin from cow’s milk to a dish of osteoblasts, the bone cells grew more quickly. When they injected lactoferrin into the skulls of five lab mice, the bone at the site of the injection also grew faster, leading the team to suggest in the journal Endocrinology that lactoferrin may play a role in treating osteoporosis. No surprise to the Department of Nutrition Sciences at the University of Arizona, where a study done with scientists from the University of Arkansas and Columbia University shows that women in their 40s, 50s, and 60s who get about 18 milligrams of iron a day have stronger, denser bones than women who get less iron. What makes this intriguing is that 18 milligrams a day is more than double the current RDA (8 milligrams) for older women.

But the iron/calcium dance is a balancing act. In your body, iron and calcium appear to compete to see which one gets absorbed. So the extra iron works only for women who get about 800 to 1,200 milligrams calcium a day — women who get less and women who get more don’t seem to benefit from extra iron.

Finally, please note that the word bones begins with b — as in vitamin B12. The female sex hormone estrogen preserves bone; the male sex hormone testosterone builds new bone. As people age and their supply of sex hormones diminishes, they lose bone faster than they can levels of vitamin B12. A report in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism says that researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, found that women with lower levels of this vitamin also have less dense hip bones. So to protect your bones, you need calcium, zinc, iron, and vitamins D and B12, all found most abundantly in milk, cheese, eggs, and red meat. Which sounds like a cardiologist’s nutritional high-fat, high-cholesterol nightmare — unless you edit the menu to read: skim milk, low-fat cheese, egg whites, and lean beef. Way to go.

No comments:

Post a Comment